As of late I’ve been doing a lot of aurora hunting, often heading off to the coast at a moment’s notice to try and catch the green and red dragon. Though I’ve been successful once, and had a few “near misses”, it’s been fun, and I’ve learned a lot about the sun, the earth, as well as the various satellites floating around earth (in particular the ACE space craft and it’s awesome near realtime data that makes sites like Aurora Services as well as apps like my own app-aurora for the Ninja Sphere possible).

I’m also a member of the Aurora Hunters Victoria Facebook page, where people share info and photos, plus tip each other off about upcoming auroras. On the page I’ve seen a bunch of questions from newcomers, and thought I’d jot down some of my own learndings about auroras. I’m no expert, so a lot of my info may be way off, but this is based on what I’ve read and experienced.

What causes an aurora?

The sun is not a uniform ball of gas. It’s much like a gigantic fiery ocean, with waves and such. When a large wave occurs, the sun spews out solar particles. If the particles are heading towards earth, the right conditions could cause an aurora due to the particles causing disruption to the earth’s magnetosphere. My experience shows that there are three key metrics for an aurora: Particle speed, particle density and Bz, all three of which, we’ll discuss later.

Be sure to check out this video by It’s Okay to be Smart, which gives an amazingly simple rundown of what causes an aurora.

Predicting

Predicting an aurora is hard, because the sun is so unpredictable. You might see 3 day aurora forecasts, but the most accurate predictions occur about an hour prior, as that’s when the particles hit the ACE spacecraft and the info reaches earth. The forecasts are usually worked out by watching for telltale signs of the sun getting ready to spew out particles. There’s no spacecraft closer to the sun and if there were, the particles might scatter out too far, mostly missing the earth, which would still make predictions inaccurate.

A lot of sites use a Kp index to determine or predict aurora “strength”, but this isn’t the best way to determine activity, as I’ve personally witnessed an aurora out at Inverloch that was Kp 5 at it’s strongest, and Kp 7 at it’s weakest. As mentioned above, Speed, Density an Bz are your three keys.

So in short, you can ask “will there be an aurora on X day of the month”, but know that the answer will be as accurate as asking “will it rain on the 12th of December in three years’ time?”. Best bet is to watch sites like Space Weather to work out when solar flares are going to happen and where they’re directed.

Speed, Density and Bz

These seem to be the key three for seeing an aurora. The theory behind them goes something like this:

Speed

Speed is like throwing a baseball. The harder you throw, the more damage it does when it hits something. The faster the particles are travelling, the brighter they’ll be as they smash into other particles in our atmosphere

Density

No, I’m not talking about Lorraine McFly (nee Baines) from Back to the Future. The more particles (i.e. the denser) that hit earth, the more intense the show will be. Going back to our baseball analogy, throwing a thousand balls looks cooler than throwing a handful

Bz

The ‘z’ is an orientation. There is also Bx and By, but generally aurora information sites don’t really worry about those. They’re available from the ACE spacecraft data site if you want to find out their values, but I don’t know how important they are. I’m still wrapping my head around Bz, so I’ll update this when I get a grasp on it, but Dartmouth’s “A Guide to Understanding and Predicting Space Weather” says:

The most important parameter is Bz, the z–component of the sun’s magnetic field. When Bz goes negative, the solar wind strongly couples to the Earth’s magnetosphere. Think of Bz as the door that allows transferring of significant amounts of energy. The more negative Bz goes, the more energy that can be transferred, resulting in more geomagnetic activity

Basically, the more negative Bz is, the more solar wind can get through and put on a good show.

Location and time

Finding a good spot is relatively simple if you’re just there to shoot the aurora, and don’t care what foreground features are present. Simply find the darkest, most southern (or highest, if you’re too far away from the coast) spot you can find, and point your camera south. Because the sun does what it wants, the particles could hit at noon. You obviously can’t see an aurora during the day, in the same way that a torch is less effective during the day, so if a big storm hits during your lunch break, ain’t nothin’ you can do about it.

If you’re located in the city and aren’t sure where to go, use Google Maps. Open it up, find your house, then look for remote spots away from towns, major roads and such. I live near three power stations so I have to travel a bit to get away from their warm glowing warming glow.

If you’re heading out somewhere new or remote, take a friend. Most non-astronomically inclined friends would be overjoyed to accompany you in the viewing of lights in the sky.

If you’re still not sure where to go because you exist in a world without Google maps (hey, it could happen!), then lots of people go coastal, to places including the Flinders blowhole, Cape Schanck, Inverloch, Cape Patterson and the other side of Melbourne to places along the great ocean road. Basically, if it’s dark and near the cost, it’s a good place.

Photographing the Aurora

Asking what exact settings to use is like asking how much fuel you’ll need to drive to a random spot in Melbourne from a random spot in Victoria. You could give a ballpark figure, but if you wanted a more exact number, you’d have to think about traffic, roadworks, alternate routes, stopping for maccas, fuel economy, tank capacity and so on.

What you should do, is practice beforehand. Go outside and shoot the stars. Know how the street lights affect your shots. Know roughly what your camera settings do and don’t be afraid to experiment. Digital storage is cheap, so just keep hammering the shutter and dicking around with the settings on the camera until you get something good. Here’s what you’d need to know at a minimum:

Shutter Speed

This is how long your camera lets light in. The longer it’s open, the more light gets in and the brighter your photos are. You need to remember that the earth is constantly moving, so if your shutter is open TOO long, you’ll get star trails which would make your photo look blurry. This can be partially resolved with..

ISO

ISO is the digital equivalent of film sensitivity. ISO determines how sensitive your camera is to incoming light. Set it low, your image will be darker. Set it high, your image will be brighter, but will also get noise (graininess). You can probably already see the relationship between shutter and ISO. Shooting the night sky is about finding the right mix.

Many lower-end cameras might have a maximum ISO of 3200 or so, while higher-end cameras can go up to 64,000. Newer cameras have better noise reduction, so the graininess isn’t as pronounced on a newer camera as it is on an older one.

Aperture

This is another “light determining” setting (which, face it, photography is all about controlling light). Your typical lens has a set of blades inside which form a circle. Remember the intro to James Bond movies with Bond shooting at the camera? The black surround is what aperture blades look like. They open or close to let more or less light in, and are like the pinhole on a pinhole camera.

Aperture is referred to as “f-stop”. If you see f/4, the aperture is wider than f/16. The higher the aperture, the sharper the photo (due to light bending) but also the less light that gets in. For shooting at night, you generally want this “open” (at it’s lowest number). If you’re shooting epic exposures (30 minutes+), you’d want to bump up the aperture, but practice lots beforehand

A good practical demonstration of aperture, is to put your index and middle fingers together, open them slightly, and peer through the gap. The scene might look darker, but it might also be sharper.

JPEG vs. RAW

Many DSLR cameras have the option to shoot in JPEG or RAW. Both have their advantages, but if you’re new to photography, I strongly suggest you shoot RAW + JPEG (grab your camera’s manual and look it up), for reasons I’ll explain. If you’re getting better with your camera, switch to RAW exclusively and don’t look back. I don’t recommend you shoot JPEG only.

JPEG

A JPEG is just a standard old image. Most images you view online would be JPEG, as it’s perfect for photos — it’s standardized, shrinks down well, can be opened on almost every computer in the world and can have variable quality, so a massive image can load rather quickly. The downside is that it’s what we call “lossy” — whatever is saving the file has no real qualms about tossing out information. That information could be merging 100 shades of red into 1 “close enough” red, or it could be a small detail in the background that nobody would look at.

RAW

RAW is a generic term that refers to file types such as CR2 (Canon), NEF (Nikon), ORF (Olympus) PEF (Pentax) and ARW (Sony). It’s basically the untouched image from the camera’s sensor. With a JPEG, as soon as it’s converted, you lose quality as mentioned above, whereas RAW is “lossless” and retains all information. RAW is supported by major apps like Photoshop, Lightroom and others, plus many online services such as Google Photos. I believe Windows 10 is starting to support it natively too. Sure the file size is bigger (up to 20+ times in some cases) but it’s worth it, because you can (to a certain extent) bump up or tone down the brightness, use them in HDR photos and even fiddle with white balance. And with most RAW formats being 12-14 bits, they can hold between 4096 and 16384 shades of colour, compared to JPEG’s paltry 256 colours. So if you’re not shooting in at least RAW + JPEG, put your camera away, please. Your hard-drive might groan, but your future-photographer-self will thank you for it. I speak from experience! 🙂

White Balance

Frankly, white balance is of little importance to me when shooting RAW, as I can simply change it later in Photoshop or Lightroom. The only time it matters to me, is when I want to see how the image looks on the back of my camera. Otherwise I’ll just ignore it. White Balance determines how warm or cool your photo looks. It’s also called colour temperature and it’s measured in Kelvins, with lower values meaning bluer photos, and higher values meaning more orange photos. Generally, just shove it on auto and fire away. Changing white balance in Lightroom doesn’t ruin your photos, so don’t panic too much about this.

Shooting Mode

Anything other than Auto. Anything other than Auto. Anything other than Auto. Anything other than Auto. Anything other than Auto. Anything other than Auto.

Got that? If you shoot an aurora in auto mode, you’re gonna have a bad time. I highly suggest manual. Sure it might be a bit complex, but you’ll have the most control and will be able to quickly set everything up for hassle-free shooting. If you’ve fiddled with your camera settings enough to know what each do, then manual is a piece of cake!

Focusing

Focusing doesn’t work in the dark. Full stop. Well it kinda does, but it’s like trying to hit a squirrel with a stone in the dark. Possible, but difficult. The best trick I learned (which came from Royce Bair’s excellent book on astrophotography) is to focus before you leave home. Point your camera at something distant and focus on it (e.g. a house down the road, the other end of your loungeroom etc.) and mark the spots with masking tape so you can easily see where you were focused. If you couldn’t plan that far ahead, get a friend to stand a bit of a distance away, pointing a torch at themselves. Focus on them, then slip your camera into manual focus to avoid hitting the shutter and losing your spot.

Tripod

Bring a tripod. That should be an “uh duh!” moment, but I’ve left home without my tripod connector before, meaning it was as good as resting my camera on a moving animal. If you find that you do forget your tripod, rest your camera on a flat rail, or prop it up with a rock or stick. Just be extra careful, as you’re more likely to drop or step on your camera

Actually shooting the aurora

I have a “favourite” setting when shooting the night sky. It usually works out to be ISO 3200, 15 second shutter speed and aperture set as open (low) as it’ll go (f/4.0 on my lens). That is slow enough to let light in, but not slow enough to cause movement. ISO 3200 ensures I don’t dip too low, while keeping my images as noise free as possible. If I catch you blindly setting these settings without knowing why you’re doing that, I’ll slap you, as these settings work for me sometimes, but if you’re closer to light pollution or in the middle of nowhere, your settings will need to change.

Shooting the aurora is as simple as setting your desire settings, pointing south and shooting. If your settings are correct, you should easily be able to see an aurora. If not, check your aurora data to ensure the aurora is strong enough to be photographed. And double check that you’re pointing south. Even if you’re staring across the water, you could be in a bay facing back towards land. I know this from personal experience out at Cape Liptrap.

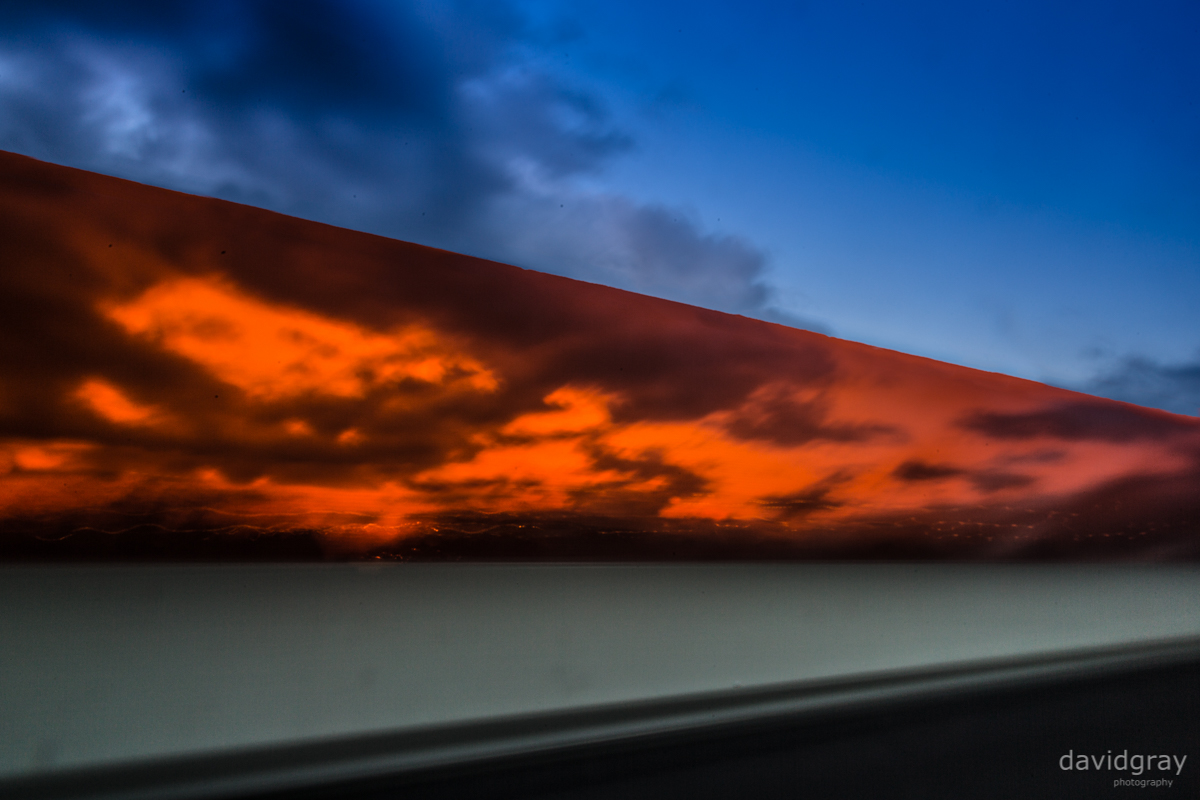

What an aurora looks like to the naked eye

When you view the aurora with the naked eye, it’s not as pretty and red or green as it looks in your photos. This is basically because of the wavelength of red and green and detection by the human eye. When I first saw the aurora after pulling up at Inverloch, it looked like light pollution in fog off in the distance. It was an extremely dull greeny orange. Then when I saw the beams off to the right, they looked like people standing in fog shining odd shaped, slightly reddish lights in the air. I knew not to trust my eyes, and sure enough, my first photo yielded a blast of pink and green colours.

Links and stuff

Everyone likes links! So here’s a bunch that’ll help you become a better photography-type-person. Here’s some great links:

Education

- The Arcanum – This site is a paid site (roughly $70 a month) but puts you in a group led by a world class photographer. You complete photographic challenges and “level up”. You also get access to the Grand Library, which is hundreds of videos about everything photography, from how to shoot a wedding, right down to how to calibrate your monitor to get perfect prints every time. I’m a member and it’s been good value so far.

Books

- My review on Milky Way Nightscapes by Royce Bair – This book is incredible. It takes you through photographing the night sky, setting up foreground elements, post-processing and lots of other great tips.

Webcams and Weather

- A list of Victorian coastal webcams – You can use this site to check your favourite coastal spot for cloud cover before you leave home.

- Bureau of Meteorology’s cloud cover – Check this to see how the clouds have been moving over the last day or so

- Cressy Aurora Cam – A webcam in Cressy, Tasmania that shows an almost 180 degree view of the sky and can show you when an aurora is happening. Check out the sample image to compare

- Auroras.live – A website of my own creation. Shows you at a glance aurora conditions.

Saying thanks!

If this post is helpful for you and you want to give back, there’s a few ways you can do it:

- Share this post with your friends. Scroll to the bottom and find the share icons.

- Follow me on one of my social media accounts. I’m on Facebook, Google+, Instagram plus plenty more (just search for davidgrayphotography wherever photos are found!)

- Check out my store. I have prints, cards and other cool stuff for sale: davidgrayPhotography

- Help me cover server costs through PayPal or with Bitcoin: 34agreMVU8QeHu4cLLPkyw5EYdSKp6NqTV

The TL;DR version

This has been a long post. Probably much longer than any other post I’ve written, but I did it to help people learn more about their camera, while learning a bit more about auroras. Here’s the rundown if you’ve got the attention span of a creature with a small attention span:

- Fiddle with the settings on your camera. All cameras have a “factory default” setting, so don’t be afraid to explore and learn about what each setting does

- Learn about ISO, shutter speed and aperture. Shutter = how much light is let in, ISO = how sensitive your camera is to light, aperture = F-Stop and is like a pinhole camera. Bigger pinhole, more light.

- Focus your camera before you leave home, put a piece of tape on your focus ring so you know where to focus when you’re in the dark.

- Use a tripod. Don’t have one? Any flat, steady surface will do, but be careful. It’s your camera!

- Shoot RAW. If you don’t wanna, shoot RAW + JPEG instead. Shooting JPEG only is like taking a photo of a Picasso masterpiece and trying to print it — it’s gonna come out “alright”, but it could be SO much better.

- Digital storage is so cheap, so don’t be afraid to take lots of photos and experiment.

- Head south. As far south as you can go. Can’t get south? Get up high.

- Go somewhere dark. Where? Get out Google Maps and look at your home, then move around until you find somewhere that’s away from major roads, away from towns, and preferably behind a hill (as hills block out lights really well). Take a friend. It’s lonely, spooky and potentially dangerous out there.

- It’s difficult to predict an aurora. A meteorologist can’t reliably predict the weather, nor can space weather sites. Accurate predictions are accurate up to an hour in advance, but keep an eye on space weather sites, as they often report potential solar activity, which could, with the right conditions, lead to an aurora.

- ISO 3200, f/4.0, 15′ Shutter speed. Those are my “starting out” settings, but don’t just blindly use these numbers. Find out what they mean and tweak them to your conditions